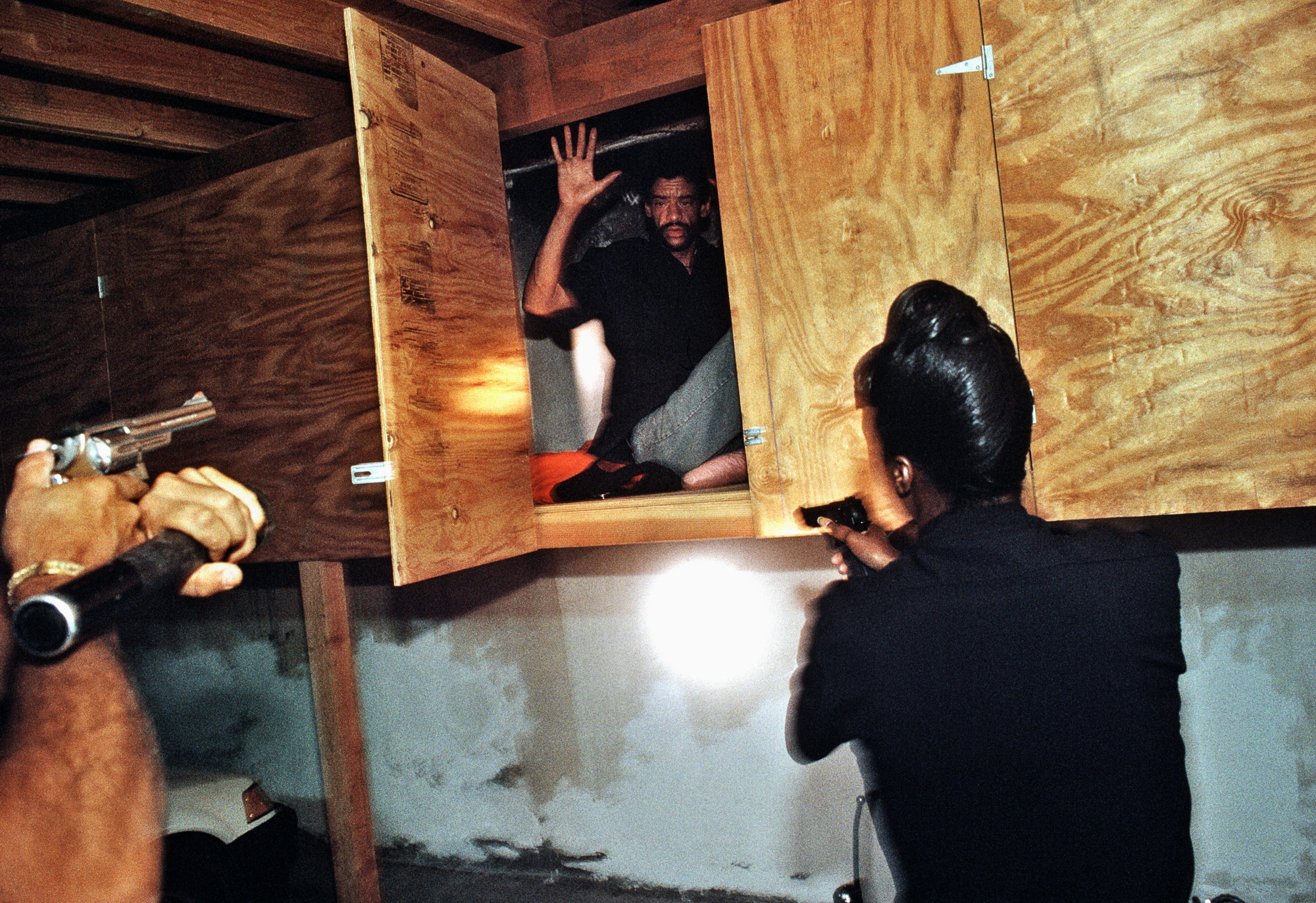

Joseph Rodríguez Rampart officers search an abandoned motel for a murder suspect in Los Angeles, 1994. The building is just a few blocks ...

Rampart officers search an abandoned motel for a murder suspect in Los Angeles, 1994. The building is just a few blocks from Charlie Chaplin’s old mansion.

In 1994, photographer Joseph Rodríguez was given unprecedented access to cover the Los Angeles police for two weeks for the New York Times. This was three years after the beating of Rodney King was recorded on video and two years after the riots broke out over the acquittal of the four officers involved, prompting a reckoning over use of force that is as familiar as it is unresolved today.

Rodríguez, a well-known documentary photographer who grew up in Brooklyn and who is no stranger to the criminal justice system, was sent to document a police force that was trying to overhaul its image within the community. The unit he embedded with, named the “Rampart Division,” is now notorious for a corruption scandal that broke a few years later. At the time, Rodríguez watched and documented cops on responding to shootings and domestic violence calls, pulling guns on gang members, and patrolling neighborhoods day in and day out.

In an age when a lot of interactions with the police are captured on cellphone videos and shared on social media, it is striking to see images that document the complex role of officers both on and off duty. The photos by Rodríguez highlight the questions that we are still grappling with today about justice, force, racism, and who gets to enact violence against whom. Although they were taken over two decades ago, the photos offer insight into how the police see themselves, a crucial thing to understand as we reckon with who we are as a society. Rodríguez has turned the work into a new book, LAPD 1994. The photographs are also on exhibition at the Bronx Documentary Center (and, conveniently, online). He spoke with BuzzFeed News about his complicated feelings about cops and how a social documentary can help shift narratives.

Rampart Division Officers detaining an arrested man, Los Angeles, 1994.

A police officer inspect the wounds of Rita Luna, a mother of seven who was beaten by her husband as the children watched until a neighbor called 911, Los Angeles, 1994.

How did this assignment start?

When this project came up, I was coming off of two years of really deep investigative work on LA gangs. I was really burned out, but one thing I’ve learned from Gilles Peress, the Magnum war photographer, is that whenever you get access you must take it. I knew that this was a one-shot deal. We were about to walk into a police precinct (that turned out to be wildly corrupt), but they gave me access, let me drive around with them for a couple of weeks. It was strange to be sitting in the backseat of a police car, but this time with a camera. I knew what I was looking at and just had to keep my eyes open. I knew this wasn’t going to last, so I just didn't sleep for two weeks, basically.

What has been the reaction you’ve received to showing police work with compassion?

I believe that there are a lot of good cops out here. There really are. I understand the criminal justice system and how it works. There are good people and there are bad people, but I was very mindful of this blue shield of silence.

Was I trying to make them look good? No, I'm just a humanist. So I photograph the person in front of me, and that's it. The number one crime in this country really is domestic violence. And they see this every day, and it jades you. Let’s not be naive though — Rampart [Division] was really corrupt. It was one of the most corrupt police divisions, and I only found this out after a story was published and the FBI went in there and whatever.

At the time, you had two of the most powerful gangs in Los Angeles, MS-13 and the 18th Street gang. I had photographed some of those guys, so I knew how serious these guys were. This crash unit that I drove around with, their main job was to get the guns off the street.

In a way, LAPD was like another gang. They would do things and keep things kind of quiet. The history is there in the book, and there will be an open discussion at the BDC. That will be interesting, how people read these pictures and what they mean.

Officer Llanes and his partner check out a garage where a man who was sleeping and using drugs there in the cabinets, Los Angeles, 1994.

Officer Hoskins responds to a car accident, truck has turned over to its side and driver and passenger were locked in, Los Angeles, 1994.

How do you feel about policing now?

I’ve seen things get more tense after we militarized the police. What I saw on the ground, the militarization of the police after 9/11 — just an amazing amount of money came in. There’s been buildup from Reagan, Clinton, and all of a sudden there's this barrage of police that come in like the Avengers. They don’t even talk to anyone, just grab everybody, grab the guns.

In your mind, what is the ideal role of a police officer?

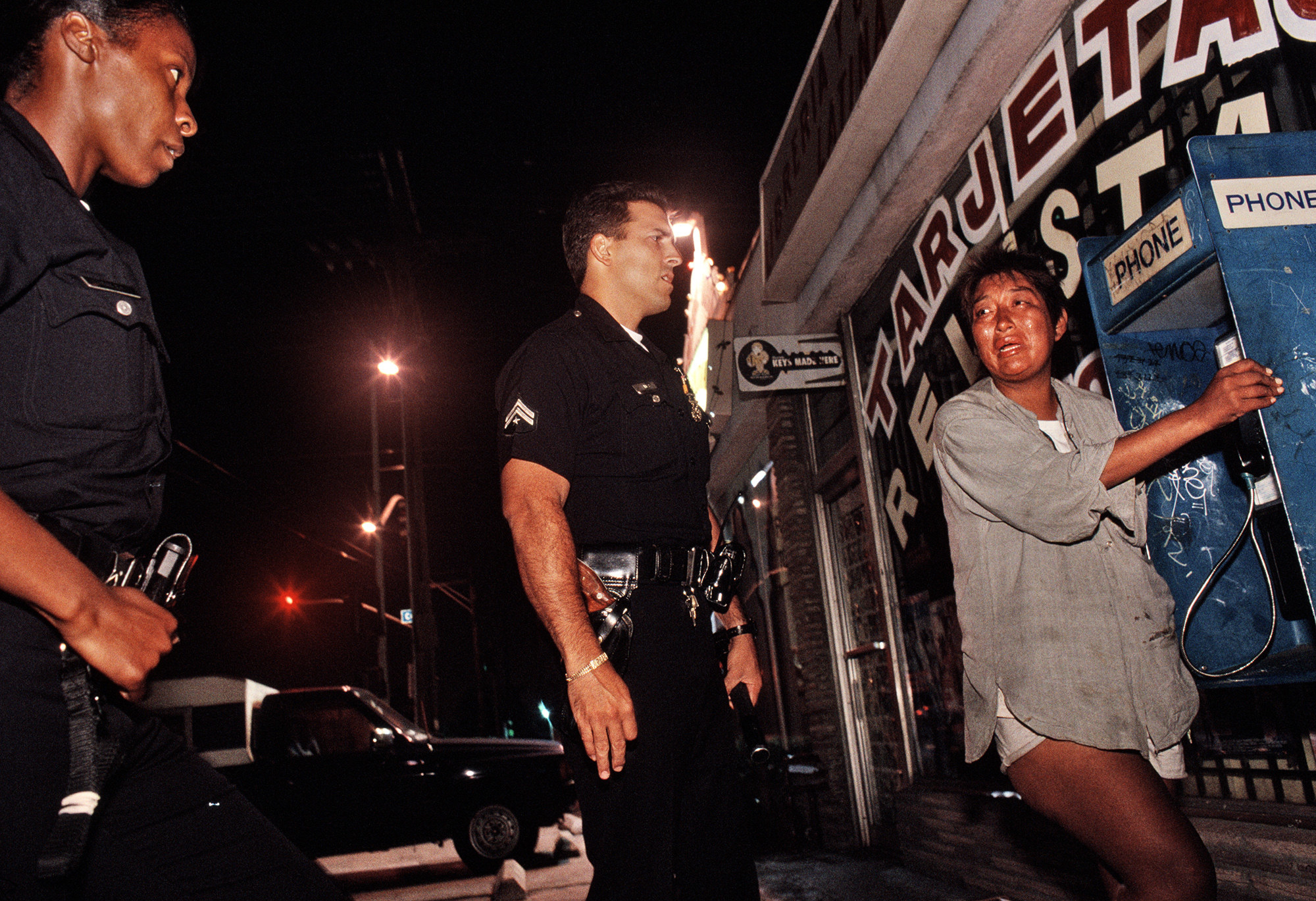

You see a little bit of it in LAPD 1994. There was Officer Llanes. They were on patrol one night, and they came across this woman. She's crying and screaming in a phone booth, and they come out. There's no guns or anything. It's a very different kind of picture. They see her every other day, and that’s community policing. They talk to her and try to get her off the streets.

In another picture, you barely see Llanes in the frame. It's a big, wide picture, and you have the father and the little kid, and it’s a domestic violence call, and he’s trying to calm things down. That's what I remember policing to be like in the ’60s and the ’70s. You had the regular officers who worked the same neighborhoods for 20 years, so they got to know the pizza place, they got to know the high school kids. So it was more of a conversation. Today it's very little conversation, and there is the latent issue of “Where do the police stand on their own race issues?” If you do the job day in, day out of these neighborhoods, I mean, whew. The guys were saying that they had more divorces than any other division. It's a tough job to do. But I’m not here to make you look good. I'm just here to show truth, show the moments. Even with my own subjective feelings and issues with the police, I kept that separate because that's the job. I'm not an activist. I’m not going in there to make you look bad either.

Officer Llanes and his partner stop and check in on a woman who lives on the streets and struggles with mental health issues.

Los Angeles police officers from the Rampart division are feeling the heat from all sides: from the mayor, from their superiors and from citizens like this man, who was assaulted by gang members and complained about the lack of police protection. This is the original caption that ran in NYT Magazine January 22, 1995.

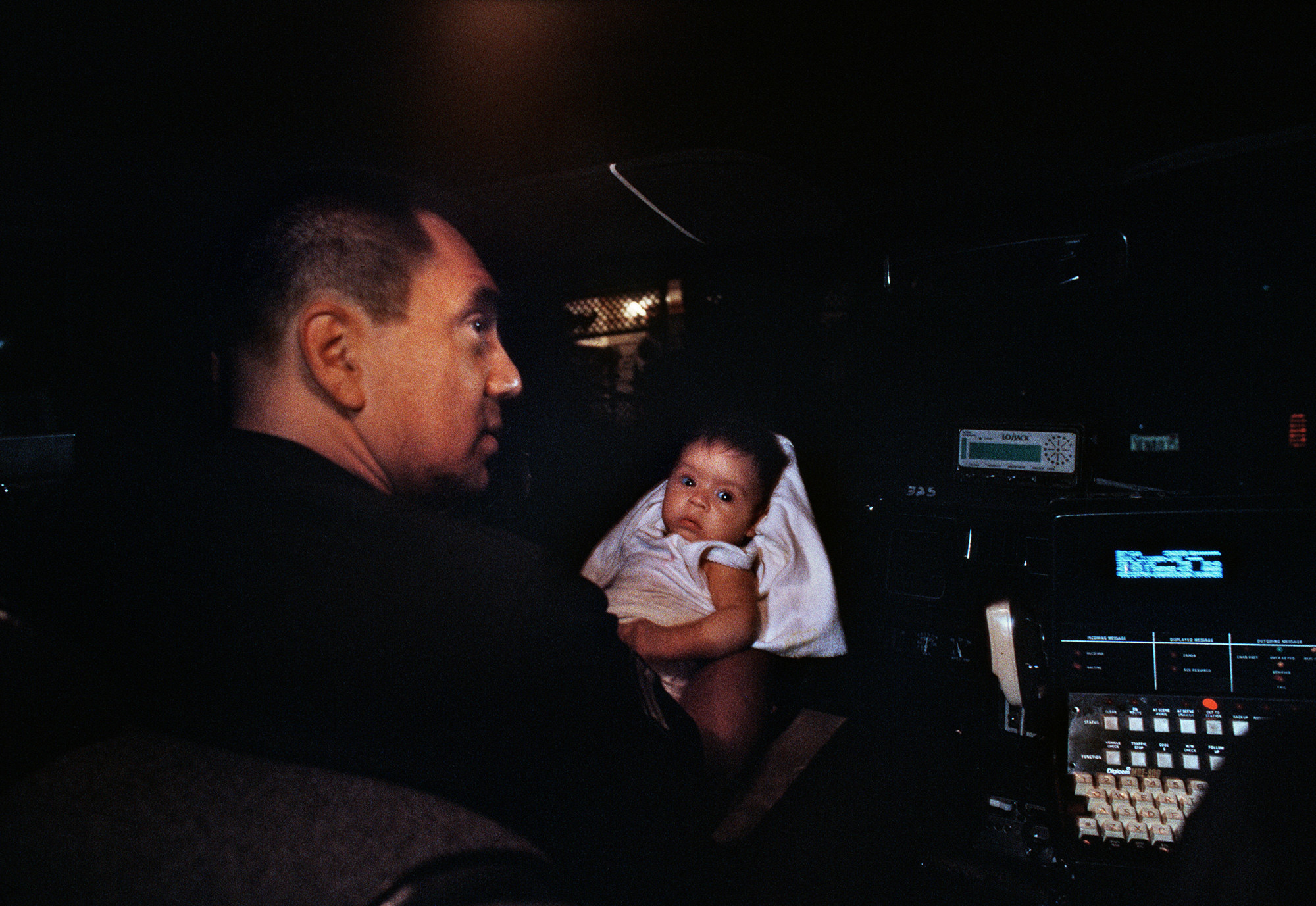

Officer Dona holds a baby from the community while on patrol, Los Angeles, 1994.

I loved that one moment where there's a new baby in the neighborhood and the officer in the car is like, Oh hey, look, there's our new baby. That's the old way. He was no angel either, but it was nice to see that humanity.

I want to make it clear — one of the things that drew me, every night, was the sheer sense of gun violence. It was like, we’d be walking down the street, 2 p.m., and there’d be some knuckleheads with a bunch of shotguns, AK-47s, shooting it out. It was really like that. I got very tired. I spent six months in therapy after this and East Side Stories [another book by Rodríguez]. PTSD is a funny thing; it builds up on you and it hits you like a ton of bricks.

What is your favorite image from this work?

I like the first picture of the police officer getting his shoes shined. There's something about that image, with the sign on the wall, “everyone here brings happiness.” Oh man, c’mon, are you serious? And you look at the face of the shoeshine guy coming in. It's just — with all the black polish coming off the box there, it represents, for me, a lot of our history. Who’s at the top, who’s doing service.

This other image that I really liked was the two detectives, the close-up, because it's so different: policing in LA versus in New York. In LA, they wear Armani suits. They’re really into that look. In New York, they wear polyester. I thought that was kind of interesting.

This is not that kind of book that makes you feel good or gives you that sense of warmth. It is a document about its particular time and what was happening. One of the other pictures that I think is almost surreal to me is the gun in the grass after this guy has just been shot. That's the evidence right there. That is America's problem right there.

Do you have any advice for aspiring photographers?

Getting access is 90% of the game. Getting that person on the other side of the phone. I know what it's like to be on the bottom. I know what it's like to be in trouble. I know what it's like to be in an angry space. I use my photography to bring some hope to something. I wouldn’t say that this is a very hopeful book, but that's OK. You can see it in my Taxi book, which is a very different book of New York at the time. I’m a social realism guy. I grew up with this social documentary practice, “Where’s the problem? What’s the problem? Let's try to make some corrections.” I believe in looking backwards at times to make sense of today.

An officer asks a victim of domestic violence to sign a restraining order against her boyfriend.

A murder suspect is arrested as his family watches.